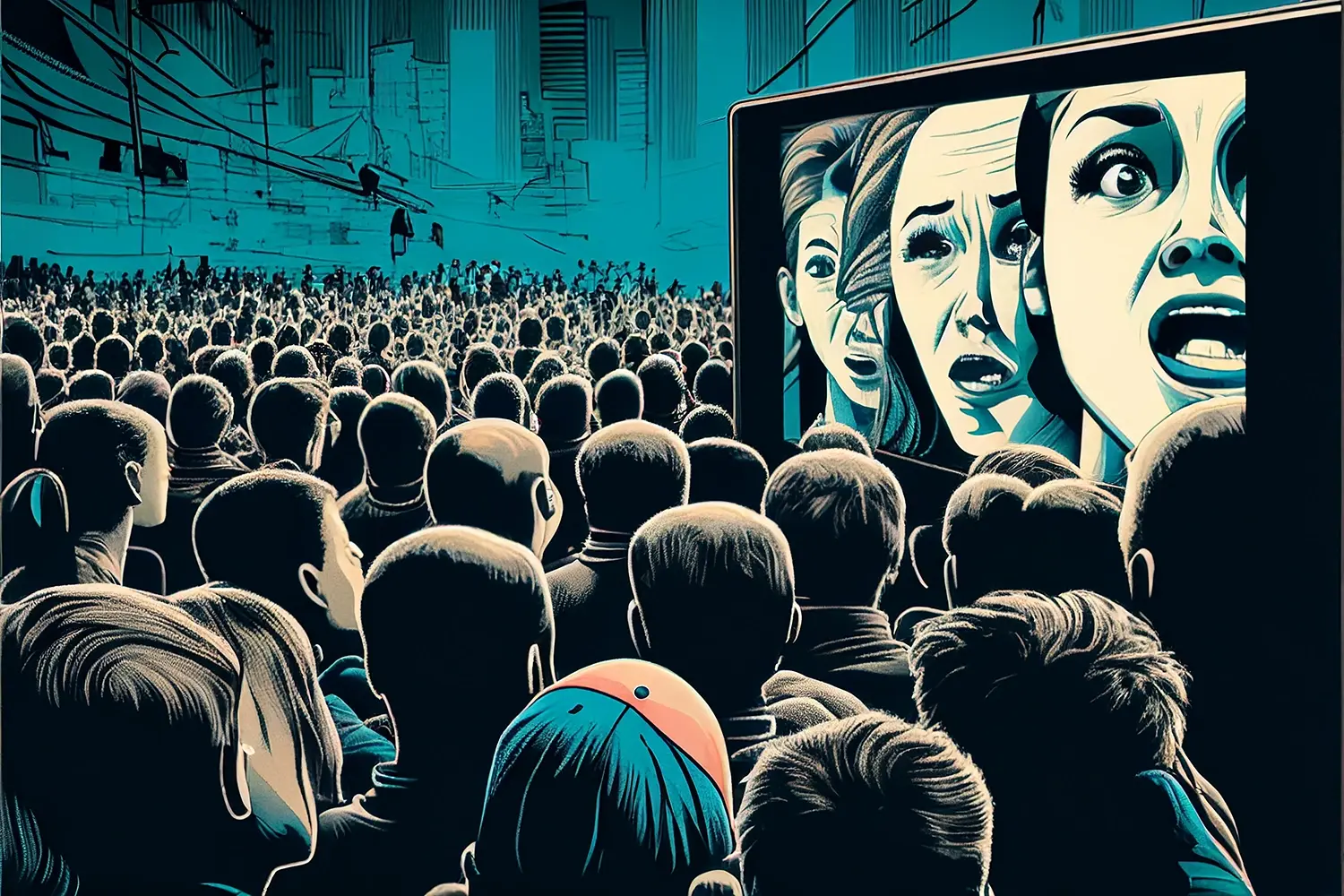

Impartiality is often thought of as the gold standard of rigorous and fair minded media. The idea that there are certain things on which we can all agree, and from these principles we can have ‘balanced’ and ‘non-partisan’ media, is baked deeply into many Western institutions. But this idea is a fantasy argues John Budarick. We need to understand that impartiality is impossible and the very belief in it justifies the prejudices and tribalism that we seek to avoid.

In 2021 Mark Ryan, then Executive Director of the Judith Nielson Institute for Journalism and Ideas in Australia, lamented how increasingly difficult it is to remain non-partisan in an increasingly complex social and political world. The blame, as it so often is, was placed by Ryan at the feet of social media, ideological tribes and a breakdown of collective faith in a known and shared world.

The speech, which carried many similar themes to others from professional journalists, commentators and politicians, reflected the ongoing faith in what can variously be called ‘impartiality’, ‘balance’ or ‘non-partisanship’. A belief that there are certain things on which we can all agree, and upon which we can base our collective social lives.

___

It is telling that such issues would affect an organisation so publicly committed to traditional journalistic norms

___

The Judith Nielson Institute is a philanthropic organisation established by billionaire Judith Nielson. Its aims include the support of ‘quality’ journalism. Like many similar ventures in the United States, where billionaire funding of news media is not uncommon, the institute is modelled on a belief that philanthropy can save independent journalism from the failures of the market and the threats of social media.

The institute has recently experienced a period of turmoil, in part due to conflicts over its direction and independence. It is telling that such issues would affect an organisation so publicly committed to traditional journalistic norms, including professional autonomy.

Concerns with independence and impartiality are common in a professional journalistic sphere that finds itself – and certainly sees itself as – under attack from various sides. Online activists, populist politicians and silicon valley billionaires are all in their own ways breaking down the role of journalism as building a consensual picture of the world upon which people can base their daily lives.

Others also draw upon discourses of impartiality in their public proclamations. Politicians in the west, faced with vociferous and sometimes overtly anti-democratic far right movements, will often appeal publicly to a sense of consensus, a view that we are all in this together and that politics is about solidarity, not ideology, conflict or antagonism

Some might even say that this form of impartial governance – where in governments seek to avoid any overt commitment to deeper ideological values and instead focus on the administrative tasks of managing economies – bears traces of the ‘third way’ of the 1990s, when ideological conflict was said to be a thing of the past.

SUGGESTED VIEWING Dangerous media for dangerous times With Matt Kelly, Alan Rusbridger

Such positions have deep philosophical roots. Western rationalism and the idea of the informed political subject are core to liberal democratic ideals. Journalistic professionalism owes much to what Stephen Ward has called the ‘objective society’ and to the scientific models of those such as Walter Lippmann. Through a scientific method, even the tumultuous world of human affairs can be known and understood in an impartial way.

___

A position of impartiality, wherein no course of action is preferred over another, is impossible

___

The problem however of such a commitment to impartiality in the sphere of social and political life is twofold.

Firstly, in imagining a social world in which impartiality is both possible and indeed desirable, such approaches fail to see their own politics. This is not to say that different levels and forms of commitment to political causes and movements cannot be ascertained. It is, however, to say that a position of impartiality, wherein no course of action is preferred over another, is impossible. As the post-structuralists would say, there is always a ‘moment of decision’.

For example, critics contend that a position of impartiality predominantly supports existing systems and structures. In this sense, the language of impartiality is employed to legitimise or obfuscate a particular political stance.

As the American Journalism scholar John Nerone has argued, this works well for those in positions of power, but not for the marginalised who push for change, sometimes radical change, at a systemic level.

The second problem relates to a more altruistic use of impartiality – as a way of saving democracy from a rising tide of anti-democratic political movements around the world.

This position – like the earlier mentioned third way politics of Tony Blair’s new Labour in England – strips politics of any notion of conflict, passion or deeply held beliefs. As the political theorist Chantal Mouffe would say, it imagines politics without ‘the political’, the inherently contingent nature of all social systems and political constellations.

___

What may be needed more than ever today is a commitment to a cause

___

As a response to anti-democratic movements, then, impartiality is rather flaccid. It imagines an impartial position that is rejected only by dangerous ideologues, regardless of their politics.

The merit of ideas is not so much judged by their commitment to equality, to emancipation of the subjugated and oppressed, but by its commitment to a sensible middle ground that we can all agree on.

There is indeed growing scepticism of such an approach. It can be seen in a rising dissatisfaction with the establishment politics of major political parties. It is also sometimes loudly proclaimed by young journalists, particularly non-white journalists, who see the perpetuation of racial inequality under the guise of ‘objectivity’.

These are journalists who reject the need to platform racist or fascist voices under the auspices of a duty to cover all important political positions. As they are well aware, the news audiences receive is the outcome of a series of decisions, decisions which will always leave some perspective excluded. Why not, they might suggest, decide to exclude the voices of white supremacists?

Rather than a stubborn commitment to impartiality, what may be needed more than ever today is a commitment to a cause, and a recognition that no position could ever transcend the messiness of human life.

Join the conversation