The glorification of the “real” in Western societies is reaching new heights. Or perhaps new lows, I should say. Craving the “real” to satiate ourselves, we eagerly embark on the quest to find our “real” and “authentic” self, without giving much thought to the cost. After all, even in the midst of the haunting fear of failing in any of our social roles, one of our greatest fears is—as Richard Rorty has accurately pointed out—the horror of finding oneself “to be only a copy or a replica.”[1]

But what kind of a promise does the idea of authenticity hold that makes it so desirable? Well, the strongly simplified answer is that it holds a promise to provide an “inner bastion”—a sanctuary offering a strong sense of self and purpose in a rapidly changing environment. But several critics have argued this is an illusion and self-defeating. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno warned that the “liturgy of inwardness” is an empty substitute for lost ethical values, and it relies on a crude picture of the self-possessing individual.[2] The historian Christopher Lasch warned that the quest for authenticity regresses into narcissist behavior that may actually undercut a stable sense of self.[3]

Still, one might think that the “inner bastion” can at least offer some protection from the influence of expanding market forces that promote conformism and compliance. This could occur in the realm of work, which has stereotypically been depicted as a social sphere where individuals relinquish their personal values and commitments that define who they are. On this point, critics like sociologist Daniel Bell were less concerned that authenticity is an illusion, but more that it adds to the erosion of the foundations of market mechanisms that are “based on a moral system of reward rooted in the Protestant sanctification of work.”[4]

Those who share this worry may feel relief in light of recent changes in the contemporary workplace. The Harvard Business Review reports that employees are now not only encouraged to “bring their whole selves to work,” but that authenticity has become the new “golden standard.”[5] At the same time, popular self-help manuals reassure that creating an authentic “personal brand” is not about distorting oneself to meet market requirements.[6] Rather, it is about discovering “who we really are,” while simultaneously communicating our “unique personal value” on the market. The logic is unambiguously articulated in the title of the widely-read self-help manual Achieve More of What You Want by Being More of Who You Are.[7]

Undoubtedly, some will react with skepticism and raise questions about the developments that have led to this peculiar turn. How is it possible that employees are encouraged to express aspects of their personhood that were once unacceptable in corporate culture? What is the nature of the changes that enable authenticity—once conceived of in terms of an “inner bastion” resistant to market requirements—to function as an institutionalized demand in contemporary capitalism?

__

"One may worry that the quest for authenticity has lost its critical potential and helps neutralize the struggle for social justice..."

___

While there is probably no single answer to these questions, two observations made by sociologists a century apart may help get it off the ground. In The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber famously argued that capitalism, being an amoral system of capital accumulation, depends on ideologies external to itself to furnish individuals with justifying reasons for participating (beyond the paycheck). Weber argued that capitalism has been able to use the ethical foundations of Protestant faith to offer a system of justification. More recently, Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello completed this picture by exposing how capitalism is able to dynamically adapt and offer new justifying reasons by incorporating and absorbing criticism.

Consider two types of criticism launched against capitalism in the 1970s. One branch, emerging in artistic and academic contexts, maintained that capitalism undermines authenticity: it distorts selfhood in part by driving a wedge between work and the private sphere as well as between “the brain and the heart.”[8] The other branch, emerging in the context of labor movements, maintained that capitalism undermines the social world: it fosters types of instrumental rationality that undermine social justice.

Since then, with declining labor movements, the second branch of criticism increasingly faded away while the first branch gained supporters and could even claim a fair amount of success. In quite a few sectors in the corporate world (but not in low-paid service jobs), the organization of work transformed to meet the demand for individuality and authenticity, reducing the constraints of hierarchical discipline. In workplaces of this kind, employees are now often encouraged to express identities and values that have traditionally been associated with the private realm.

Has this development provided novel freedoms and more room for diversity? Compared to earlier and stricter forms of management, it surely seems so. But the story is full of ambiguities. One flipside is that these changes also chip away at the aims of the second criticism.[9] For instance, while individual negotiations and contracts have allowed for part-time and flexible-time work, they have also replaced qualification-based salaries and collectively regulated benefits, creating diffuse inequalities. Consequently, one may worry that the quest for authenticity has lost its critical potential and helps neutralize the struggle for social justice, ultimately broadening the range of instruments through which the market sphere expands beyond traditional constraints. The “be yourself” discourse may then regress into little more than a thinly veiled scheme of exploiting the hitherto untouched reservoirs of the self.

Offering a comprehensive social criticism of these developments requires a reorientation, starting with focusing on the right questions. Instead of rejecting the pursuit of authenticity as an empty fantasy, the task is to investigate how understanding what it means to be authentic has transformed in light of market demands. This will provide the backdrop to recast and promote authenticity in terms of an individualism that does not promote self-absorption, but draws its normative force from a commitment to social justice.

Adorno, Theodor W. (1973) The Jargon of Authenticity, trans. Knut Tarnowski and Frederic Will. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Bell, Daniel (1976) The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. New York: Basic Books.

Boltanski, Luc and Chiapello, Eve (2005) The New Spirit of Capitalism. London: Verso.

Fleming, Peter (2009) Authenticity and the Cultural Politics of Work: New Forms of Informal Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ibarra, Herminia (2015) “The Authenticity Paradox” Harvard Business Review, January/February.

Lasch, Christopher (1979) The Culture of Narcissism, New York: Norton

Rorty, Richard (1989) Contingency, Irony and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sampson, Eleri (2002) Build Your Personal Brand. London: Kogan Page.

Speak, Karl (2011) Be Your Own Brand: Achieve More of What You Want by Being More of Who You Are. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Varga, Somogy (2011) Authenticity as an Ethical Ideal. London: Routledge.

Weber, Max (2013) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

[1] Rorty, Richard. Contingency, Irony and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1989), 24.

[2] Adorno, Theodor W. (1973) The Jargon of Authenticity, trans. Knut Tarnowski and Frederic Will. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press., 70.

[3] Lasch, Christopher (1979) The Culture of Narcissism, New York: Norton (1976).

[4] Bell, Daniel. The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. New York: Basic Books.(1976), 84.

[5] Ibarra, Herminia (2015) “The Authenticity Paradox” Harvard Business Review, January/February. (2015).

[6] See for instance Sampson, Eleri (2002) Build Your Personal Brand. London: Kogan Page.

[7] McNally, David and Speak, Karl. Be Your Own Brand: Achieve More of What You Want by Being More of Who You Are. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. (2011).

[8] See Boltanski, Luc and Chiapello, Eve (2005) The New Spirit of Capitalism. London: Verso. 2005, 96–99.

[9] For a discussion, see Fleming, Peter Authenticity and the Cultural Politics of Work: New Forms of Informal Contro

The glorification of the “real” in Western societies is reaching new heights. Or perhaps new lows, I should say. Craving the “real” to satiate ourselves, we eagerly embark on the quest to find our “real” and “authentic” self, without giving much thought to the cost. After all, even in the midst of the haunting fear of failing in any of our social roles, one of our greatest fears is—as Richard Rorty has accurately pointed out—the horror of finding oneself “to be only a copy or a replica.”[1]

But what kind of a promise does the idea of authenticity hold that makes it so desirable? Well, the strongly simplified answer is that it holds a promise to provide an “inner bastion”—a sanctuary offering a strong sense of self and purpose in a rapidly changing environment. But several critics have argued this is an illusion and self-defeating. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno warned that the “liturgy of inwardness” is an empty substitute for lost ethical values, and it relies on a crude picture of the self-possessing individual.[2] The historian Christopher Lasch warned that the quest for authenticity regresses into narcissist behavior that may actually undercut a stable sense of self.[3]

Still, one might think that the “inner bastion” can at least offer some protection from the influence of expanding market forces that promote conformism and compliance. This could occur in the realm of work, which has stereotypically been depicted as a social sphere where individuals relinquish their personal values and commitments that define who they are. On this point, critics like sociologist Daniel Bell were less concerned that authenticity is an illusion, but more that it adds to the erosion of the foundations of market mechanisms that are “based on a moral system of reward rooted in the Protestant sanctification of work.”[4]

Those who share this worry may feel relief in light of recent changes in the contemporary workplace. The Harvard Business Review reports that employees are now not only encouraged to “bring their whole selves to work,” but that authenticity has become the new “golden standard.”[5] At the same time, popular self-help manuals reassure that creating an authentic “personal brand” is not about distorting oneself to meet market requirements.[6] Rather, it is about discovering “who we really are,” while simultaneously communicating our “unique personal value” on the market. The logic is unambiguously articulated in the title of the widely-read self-help manual Achieve More of What You Want by Being More of Who You Are.[7]

Undoubtedly, some will react with skepticism and raise questions about the developments that have led to this peculiar turn. How is it possible that employees are encouraged to express aspects of their personhood that were once unacceptable in corporate culture? What is the nature of the changes that enable authenticity—once conceived of in terms of an “inner bastion” resistant to market requirements—to function as an institutionalized demand in contemporary capitalism?

__

"One may worry that the quest for authenticity has lost its critical potential and helps neutralize the struggle for social justice..."

___

While there is probably no single answer to these questions, two observations made by sociologists a century apart may help get it off the ground. In The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber famously argued that capitalism, being an amoral system of capital accumulation, depends on ideologies external to itself to furnish individuals with justifying reasons for participating (beyond the paycheck). Weber argued that capitalism has been able to use the ethical foundations of Protestant faith to offer a system of justification. More recently, Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello completed this picture by exposing how capitalism is able to dynamically adapt and offer new justifying reasons by incorporating and absorbing criticism.

Consider two types of criticism launched against capitalism in the 1970s. One branch, emerging in artistic and academic contexts, maintained that capitalism undermines authenticity: it distorts selfhood in part by driving a wedge between work and the private sphere as well as between “the brain and the heart.”[8] The other branch, emerging in the context of labor movements, maintained that capitalism undermines the social world: it fosters types of instrumental rationality that undermine social justice.

Since then, with declining labor movements, the second branch of criticism increasingly faded away while the first branch gained supporters and could even claim a fair amount of success. In quite a few sectors in the corporate world (but not in low-paid service jobs), the organization of work transformed to meet the demand for individuality and authenticity, reducing the constraints of hierarchical discipline. In workplaces of this kind, employees are now often encouraged to express identities and values that have traditionally been associated with the private realm.

Has this development provided novel freedoms and more room for diversity? Compared to earlier and stricter forms of management, it surely seems so. But the story is full of ambiguities. One flipside is that these changes also chip away at the aims of the second criticism.[9] For instance, while individual negotiations and contracts have allowed for part-time and flexible-time work, they have also replaced qualification-based salaries and collectively regulated benefits, creating diffuse inequalities. Consequently, one may worry that the quest for authenticity has lost its critical potential and helps neutralize the struggle for social justice, ultimately broadening the range of instruments through which the market sphere expands beyond traditional constraints. The “be yourself” discourse may then regress into little more than a thinly veiled scheme of exploiting the hitherto untouched reservoirs of the self.

Offering a comprehensive social criticism of these developments requires a reorientation, starting with focusing on the right questions. Instead of rejecting the pursuit of authenticity as an empty fantasy, the task is to investigate how understanding what it means to be authentic has transformed in light of market demands. This will provide the backdrop to recast and promote authenticity in terms of an individualism that does not promote self-absorption, but draws its normative force from a commitment to social justice.

[1] Rorty, Richard. Contingency, Irony and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1989), 24.

[2] Adorno, Theodor W. (1973) The Jargon of Authenticity, trans. Knut Tarnowski and Frederic Will. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press., 70.

[3] Lasch, Christopher (1979) The Culture of Narcissism, New York: Norton (1976).

[4] Bell, Daniel. The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. New York: Basic Books.(1976), 84.

[5] Ibarra, Herminia (2015) “The Authenticity Paradox” Harvard Business Review, January/February. (2015).

[6] See for instance Sampson, Eleri (2002) Build Your Personal Brand. London: Kogan Page.

[7] McNally, David and Speak, Karl. Be Your Own Brand: Achieve More of What You Want by Being More of Who You Are. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. (2011).

[8] See Boltanski, Luc and Chiapello, Eve (2005) The New Spirit of Capitalism. London: Verso. 2005, 96–99.

[9] For a discussion, see Fleming, Peter. Authenticity and the Cultural Politics of Work: New Forms of Informal Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2009) and Varga, Somogy. Authenticity as an Ethical Ideal. London: Routledge. (2011)

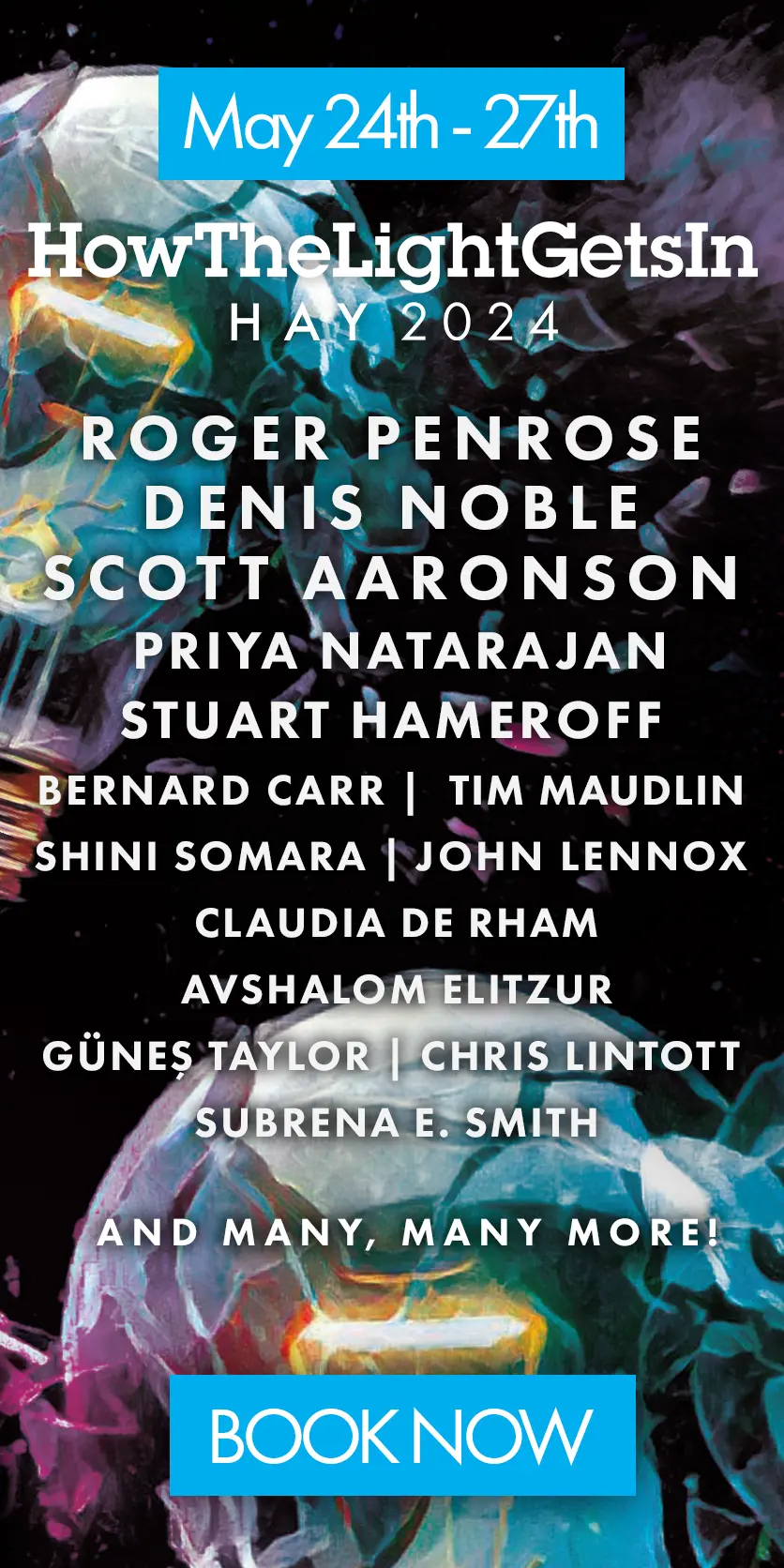

Debate the biggest ideas of our times at the Institute of Art and Ideas' annual philosophy and music festival HowTheLightGetsIn. For more information and tickets, click here

Join the conversation