Socrates was sentenced to death for corrupting the youth of Athens. Why? He had publicly questioned the authority of the city's gods to legislate how we should live. His more or less explicit prioritisation of ethics over state religion was subversive. If social moral standards are not dependent on the whims of the gods – if the gods don’t determine the standards we should live by – then individuals appear to be licensed to think for themselves.

Plato, who agreed with his teacher that gods can’t underwrite social morality, postulated a realm of transcendent value in the place of gods. Where a god might command and punish, Plato’s transcendent value was supposed to inspire and be loved by all who glimpsed it. Nietzsche went further, proclaiming the death of God and of transcendent value too. On his proposal, conventional social morality is only an ideological social construct developed by the physically weak to subjugate the physically strong. An all-powerful ethically authoritative god is a rhetorical conceit to sustain an illusion of transcendent value – an illusion that we would do better without.

If we cease to believe in the existence of gods or transcendent value, is there yet any reason to act as social morality requires? Can our practices survive even if their imagined foundations are exposed as sham – just as Christmas celebrations might survive without belief in Jesus or Santa Claus? If we give up belief in gods or transcendent value but continue to hold everyone to conventional moral standards, is it, as Elizabeth Anscombe writes in 1957, “as if the notion ‘criminal’ were to remain when criminal law and criminal courts had been abolished”?

Not everyone needs the prospect of divine rewards or punishments to be motivated to do what social morality requires. Plenty of people care about others directly; and when the wellbeing of others is a condition for your own happiness, social morality has its own rewards. So one way to answer the question, “why uphold social morality in a godless world?” is to capitalise on the ways in which people already care about each other. Aristotle, Rousseau, Mill, and others, in different ways develop the idea that we are fundamentally social or cooperative animals, whose flourishing depends on acting in cooperative social ways (and not merely contingently, as one might happen to take pleasure in wearing a jacket in a clubroom or maintaining one’s membership in a club). If we are fundamentally social selves, then the flourishing of each and every individual and of society as a whole will necessarily tend to coincide.

In his ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’, Isaiah Berlin challenges the idea of an essentially social or cooperative self as yet another myth propagated to satisfy a yearning for moral absolutes. Belief in a social self is a consoling motivational conceit to underwrite conventional social morality and lend credence to the claim that the unsociable knave isn’t flourishing or ‘fulfilling his potential’. Berlin acknowledges the yearning for such absolutes but counsels us to resist. “To demand more than [the ‘relative validity of one's convictions’] is perhaps a deep and incurable metaphysical need; but to allow it to determine one's practice is a symptom of an equally deep, and more dangerous, moral and political immaturity.”

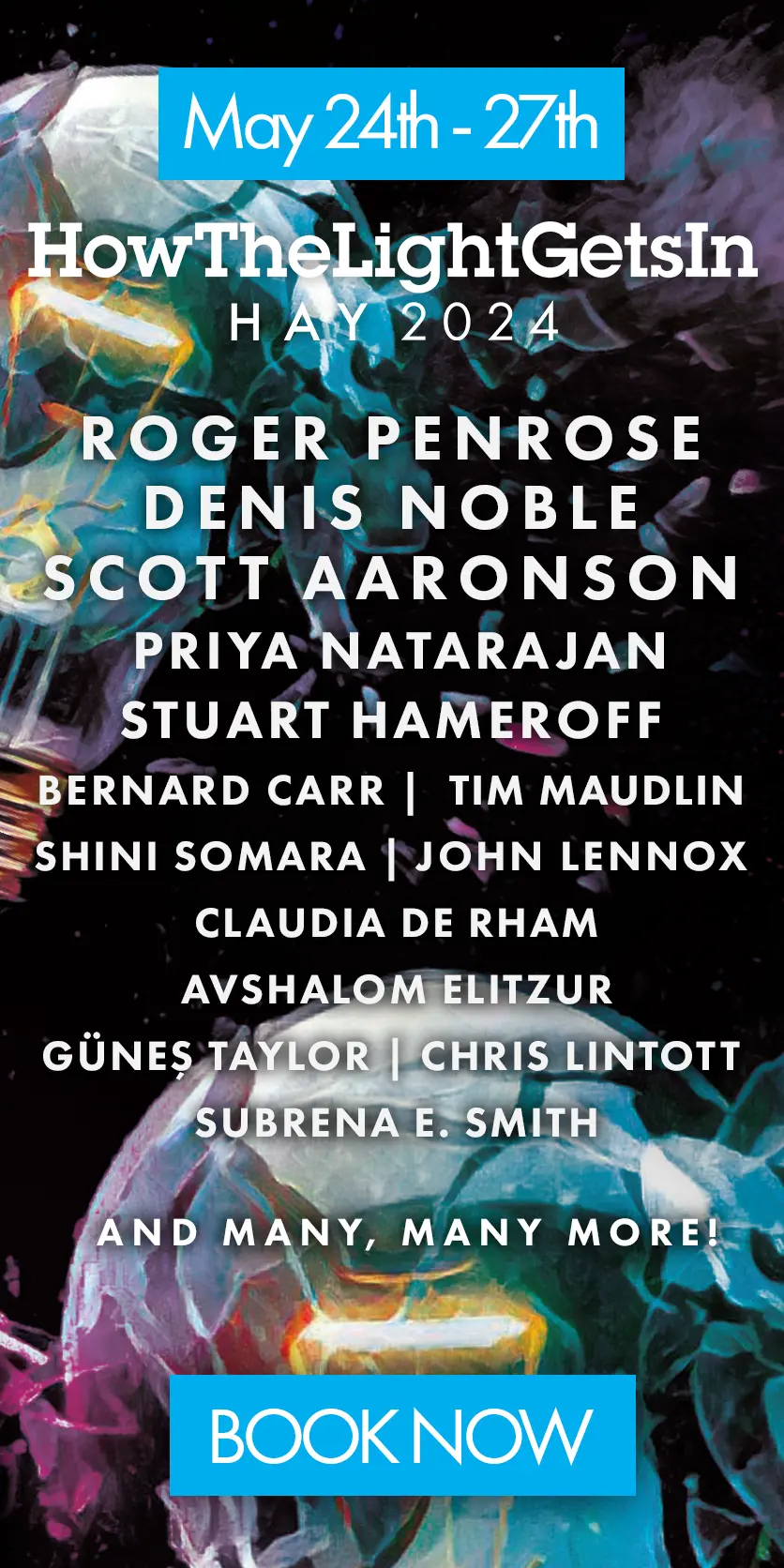

In the absence of metaphysical guarantees – whether in gods, the universe, or an essentially social self – each of us faces a task to construct, rather than discover, ideals by which to live. The process of construction will be contingent, messy, political. Will we be strong enough to engage in such construction honestly? Will anything like a universal social morality emerge? In the debate at 2015’s HowTheLightGetsIn festival I defended the interest of these questions, but I didn’t pose any answer. As I see it, the questions are empirical, and still open.

Join the conversation